The Napoleonic Wars encompassed theaters of operations throughout the world. The main theaters shifted over time but some theaters were destined to remain strategic backwaters. The Adriatic was one of those.

The Venetian Republic had ceased to exist when it was overrun by the troops of Revolutionary France in 1797. Ceded to Austria under the treaty that ended the War of the First Coalition, Venice was an Austrian province until 1805. When the Treaty of Pressburg was signed, in the aftermath of disastrous defeats at the hands of the French at Ulm and Austerlitz and the collapse of the Third Coalition, Venice was stripped from Austrian control and became part of Napoleon’s short lived Kingdom of Italy.

While the Adriatic was of little strategic import to the British it was an important source of naval stores for France and so raiding commerce in the Adriatic became a priority for the British Navy.

The French and Venetians had a fairly large naval force, on paper anyway, and endeavored to fortify many of the islands in the Adriatic so small convoys could move from one covered location to another and remain safe from British raiders.

From the British point of view this was an economy of force operation. A small number of British frigates were detailed to suppress trade in the Adriatic and one of the leading lights of this effort was Captain William Hoste.

Hoste had first been sent into the Adriatic in 1808 in HMS Amphion (32) and had wrecked havoc there, taking or burning over 200 enemy prizes. Success begets success and Hoste was sent back into the Adriatic again and again and was rewarded with command of a small squadron: HMS Active (38), HMS Cerberus (32), and HMS Volage (22). We should note here that three British frigates are the 18-pounders of the latter part of the Napoleonic Wars and despite their ratings Amphion actually carried 42 guns, Active 48, and Cerberus 38.

The area of conflict centered on the island of Lissa, today the Croatian island of Vis. Lissa was the forward operating base used by Hoste and it was a hotbed of British privateers. As such it was a target for the Franco-Venetian forces, based across the Adriatic in Ancona, Italy, trying to secure commerce in the area.

Increasingly the skirmishing between the sides took on a personal air. On October 6, 1810 the French squadron of Commodore, later Rear Admiral, Bernard Dubourdieu encountered the Amphion and Active patrolling off Ancona. Hoste decided that the five frigates and two brigs of Dubourdieu presented odds too high for even the British navy to attempt to overcome and retreated to Lissa to pick up the remainder of his squadron. Once he’d made the rendezvous he sailed to meet Doubourdieu. However, Dourboudieu took the opportunity to evade Hoste’s squadron, raid Lissa, take three of Hoste’s prizes and burn five privateers. To add insult to injury he sent a letter which was printed in Le Moniteur which insinuated that Hoste had an equal squadron but was afraid to fight.

Hoste took up the challenge and promptly bottled up Dobourdieu in Ancona. There matters might have remained until a gale in mid-October drove Volage into the side of Amphion and necessitated both returning to Malta for substantial repairs.

Hoste in Amphion and Volage arrived back at Lissa on March 7, 1811, and Dubourdieu sailed from Ancona on March 11 with a squadron consisting of the large French frigates Favorite (44) and flying Dubourdieu’s broad pennant, Flore (44), Danaë (44) and a Ventian contingent consisting of Corona (44), Bellona (32), Carolina (32), Principessa Augusta (18), Mercure (16), Principessa di Bologna (10), Ladola (2), and Eugenie (6). Dubourdieu also carried about 400 troops for the purpose of taking and establishing a garrison on Lissa.

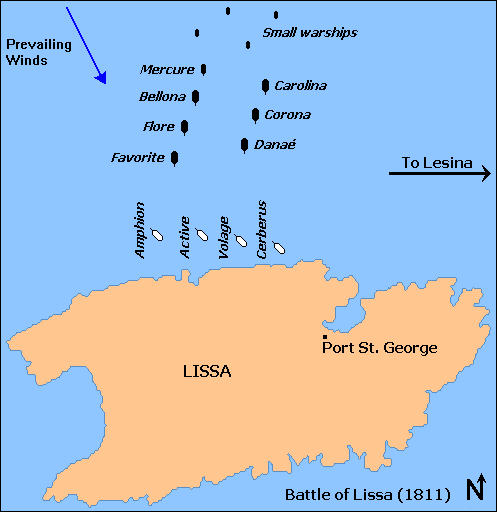

The record is somewhat unclear but it seems that word had reached Hoste that the French were coming because the night of 12-13 March found Hoste’s squadron tacking back and forth off Port St. George, Lissa. Around 3am Active, the most upwind of Hoste’s ships spotted the Franco-Venetian flotilla. Her captain, Captain James Alexander Gordon, fired two guns and hoisted a blue light to signify a strange fleet to windward. When the sun rose Hoste could see the fleet arrayed against him.

Situation at dawn on March 13, 1811. The British squadron under Admiral William Hoste discovers the French squagron to windward.

Hoste formed his ships into one division with Amphion leading followed by Active, Volage, and Cerberus, set all possible sail, and began tacking upwind to engage the French.

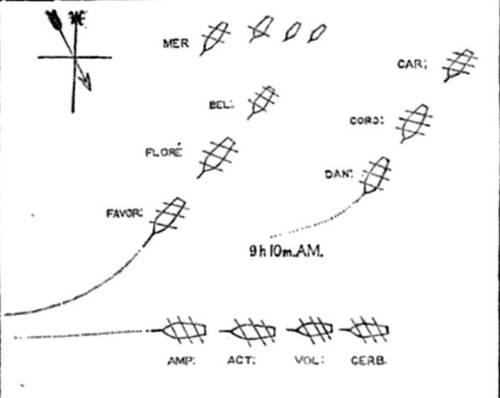

By around 6am the Franco-Venetian squadron had sorted itself into two divisions, a starboard, and in this case weather, division consisting of Favorite, Flore, Bellona, and Principessa Augusta, and a larboard or leeward division composed of Danaë, Corona, Carolina, and a gaggle of small craft.

It seems that Dubourdieu intended to break the British line in two places which would have resulted in the piecemeal destruction of the British squadron. He was stymied by the close interval kept by the British ships, with bowsprits overhanging the transom of the ship in front, which offered no opportunity to break the line. Shortly before opening fire, Hoste hoisted the signal “Remember Nelson.”

Situation at about 9am, March 12, 1811. The French squadron in two divisions bears down on Hoste's squadron attempting to break his line.

Scanned from the Naval History of Great Britain by William James

As the Dubourdieu bore down on the British, his force was heavily engaged by Hoste’s ships. Favorite, unable to break the line, attempted to board Amphion but her decks were swept by grapeshot killing or mortally wounding Dubourdieu. The two Franco-Venetian divisions converged on Hoste, until the three major combatants in Dubourdieu’s leeward division, Danaë, Corona, and Carolina, laid alongside Volage and Cerberus and began exchanging broadsides in what was a manifestly unequal match up.

Favorite attempted to wear ship to come around in front of Amphion, followed by the rest of the ships in her division, and then engage her from leeward. This would place the British squadron between the two Franco-Venetian divisions.

About 9:40am, just as Favorite was beginning her maneuver, Hoste signaled for his squadron to wear ship together which would have the effect of reversing course and allowing him to concentrate all four of his ships on the Franco-Venetian leeward division and temporarily removing the windward division from the picture. Few things go exactly as planned. Favorite had lost most of her officers in the ill-conceived attempt to board Amphion and went out of control while attempting to wear and ended up on the rocks just off Lissa. Cerberus has her rudder shot away while turning and fell out of line.

Situation at about 9:40am, March 13, 1811. The French flagship Favorite has lost its officers and beached itself. Hoste orders his squdron to wear ship in order to destroy the Franco-Venetian leeward division. Cerberus has her rudder shot away in the turn and falls off to leeward.

Scanned from Battles of the British Navy by William James

As Amphion wore ship, Flore, which was undamaged, surged ahead, raked her stern and then laid along her leeward side. At the same time Bellona wore ship and came along Amphion’s windward side. Now Amphion a 32-gun frigate was engaging a 44 and a 32.

Cerberus being out of the line now caused the leading ship in the British column to be the Volage sloop. Danaë wore ship, followed by Corona and Carolina, to cut ahead of Active and concentrate their fires on Volage. Corona and Carolina concentrated on the disable Cerberus leaving Volage — rated at 22 guns but carrying 22 32-pound carronades, 4 18-pound carronades, and two long 6 bow chasers — to slug it out with the 44 gun Danaë. Danaë retreated out of range [ed note, max range of the 32-pound carronade was about 720 yards, that of the long 18-pounder on Danaë was about 1200 yards] and proceeded to engage with her 18 pounder main battery. Volage responded by overcharging the carronades with powder to increase the range. The result was the eventual dismounting of all of her larboard carronades because of the increased recoil and having to fight Danaë with a brass 6-pounder bowchaser.

Situation at about 10:30am, March 13, 1811. Amphion is heavily engaged by Flore and Bellona. Cerberus and Volage are in danger of being overwhelmed by Corona, Danaë, and Carolina as Active comes to their assitance.

Scanned from Battles of the British Navy by William James

Corona closed with Cerberus and engaged in yet another unequal contest between a 44 and a 32. Caroline peppered Cerberus from a distance but was reluctant to actually engage in the slugfest.

Active evaluated the situation and decided that Cerberus and Volage needed her assistance more than did Amphion and started beating upwind to come to their assistance. As Active approached the battle, Danaë, Corona, and Caroline broke off combat and fled to the east.

Meanwhile, Hoste had succeeded in drawing ahead of Flore and crossed her bows at half-pistol shot, about 12-13 yards, reduced sail and laid along her starboard bow which she pummeled for about ten minutes before Flore struck her colors. So badly shot up was Amphion’s rigging and boats that Hoste was unable to send a boarding party to Flore. Instead he devoted his full attention to Bellona. He positioned himself off the weather bow of Bellona and forced her to strike.

It was not shortly after noon and Hoste hoisted the signal General Chase.

Amphion, Cerberus, and Volage were unable to pursue because of battle damage. Active set out after Corona and forced her to strike around 3pm after a spirited engagement. In the meantime, Flore had reneged on her surrender. She hoisted her flag and fled. Favorite was set afire by her crew and blew up around 4pm.

Situation at about noon, March 13, 1811. Amphion has forced Flore to and Bellona to strike. Hoste signals

Amphion lost 15 killed and 47 wounded of 251 men aboard, among the latter Captain Hoste wounded in the arm. The damage to her masts left them all on the verge of toppling. Active, which through no fault of her own was largely unengaged, lost 5 killed and 24 wounded out of 300 men. Cerberus, which was short handed from prize crews only had 160 men of the 250 she was allotted, lost 13 dead and 41 wounded. Though her masts and rigging were in good shape her hull was beaten to a shambles. Volage, who had duked it out with a 44, lost 13 killed and 33 wounded out of a complement of 175. Her masts and rigging were much damaged.

Even as the British fleet licked its wounds the outcome of the battle was very nearly nullified on the ground. Some 200 sailors and embarked soldiers from Favorite made their way ashore and marched on Port St. George with the intention of capturing it. This would have left Hoste with a very hollow victory and a great deal of embarrassment. Two midshipmen put together a scratch force of British military personnel and local citizens and went to meet this threat. The persuaded the Venetian commander that the return of the British fleet would bring overwhelming force to bear on his small detachment and he could expect better terms by surrendering to them. He did so.

Hoste sent a heated series of letters to the French naval commander impugning the integrity of the commander of the Flore and demanding the return of Flore to him as a lawful prize. Not unsurprisingly, the French declined to accommodate him.

This was a turning point in the Adriatic. From this point forward British power wasn’t seriously challenged. The remnants of the French fleet were laid up in Ragusa (or Dubrovnik, if you will) for repairs. Critical supplies for the refit were dispatched from France aboard the 16-gun brig Simplon. As Simplon worked its way around the Adriatic coast it ran afoul of Belle Poule (38), Captain James Brisbane, and Alceste (38), Captain Murray Maxwell. They drove her close up under the coastal battery at Parenzo (Poreč. Croatia) and unable to destroy her directly, the two frigates landed on St. Nicholas island at the mouth of the harbor, set up an assortment of artillery, and battered the brig to wreckage. The French were unable to repair their fleet and quietly evacuated the Adriatic. Another minor challenge arose on November 29, 1811 but it was quickly quashed. In the end, the failure to control the Adriatic effectively negated any value of Napoleon’s Italian conquests.

Pingback: Vis (Lissa), Croatia « Age Of Sail

Pingback: Captain Sir William Hoste « Age Of Sail

This is a most superior battle, they should make a movie about this and the Battle of Lake Erie.

War is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good

Pingback: Battle of Lissa (13 March 1811) – Basque Roads